July 31, 2008

Restoration

8 Comments

At the De Anza Electronics Flea Market, someone was selling a rather beat-up and rusty desk fan. But it was no ordinary desk fan, this one was quite old. I had to have it. Later on, it looked at me plaintively from my workbench.

Suddenly it hit me–I had to restore this bedraggled-looking thing!

It was a really long and involved process, taking me well over a month, but I have finally (mostly) finished. Why did it take so long? Well, for example, I found that the speed coil (basically a big inductor with taps for each speed setting) was slowly being eaten by rust. Thus began the arduous process of disassembling the entire coil, pulling apart the laminations, polishing off all the rust, varnishing them again (since the laminations must be insulated from each other), and reassembling the whole thing.

All the work really did pay off. Here is what the mostly completed fan looks like. It’s fully operational. The cotton-covered twisted line cord I purchased from Sundial Wire. The plug is actually a standard item at OSH, believe it or not. I guess styles don’t really change much. The cord the fan came with was a more modern zip cord with a quick-plug, and the replacement plug is basically a 3-prong copy of the original.

Why “mostly?” Well, the badge that goes in the center of the cage is pretty much beyond repair, and it also appears to be the wrong badge for this fan.

The badge should be brass with a slightly different logo. Regardless of whether or not this badge is original, brass would look a whole lot better. I have been trying (and failing at) various brass etching techniques, since I have the CAD drawing of the logo already.

Problem #1 is getting the toner transfer method to work. I have used magazine paper (an old issue of Nuts and Volts: my Make magazine issues deserve better!) and it really does not work for me, probably due to the amount of toner my laser printer puts out. Trust me, I tried a dozen times or so.

Problem #2 is the actual etching process. Salt tank etching was a bit too faint, so next time I will try ferric chloride, which is usually used for PC boards, but should work for brass as well.

Problem #3 is getting the etched brass sheet into the proper shape, which is convex in the middle with a rounded rim. Metal tabs in the back fold around the disc in the center of the cage to hold the badge in place.

If you have any ideas, drop me a line in the comments…

July 31, 2008

Projects

1 Comment

Somebody at Maker Faire was interested in Nixie tube jewelry that actually lit up. I decided to take up the challenge.

The hard part is not making everything small, but making it last a long time on a single battery. In this case, the battery is a CR2032 lithium coin cell. A small circuit takes the 3 volts and steps it up to about 150V which is barely enough to light the Nixie tube. Theoretically it should last around 10 hours or so.

The socket was constructed using my custom-made Dremel drill press. To figure out where to drill the holes, I put some clay on top of the wood and pressed the pins of the Nixie tube into the clay. Then it was a simple matter to mark the pin holes, remove the clay, and drill. The pins are actually from a DB25 solder tail socket, since they fit the Nixie pins perfectly.

The power supply circuit has its problems, and I am trying to improve on it.

July 31, 2008

Restoration

1 Comment

Previously I posted about a vintage Clough-Brengle oscillograph I obtained. It’s been a long process, but I’ve restored it to operational condition.

One of the first steps in the process was to figure out what needed to be fixed. In electronics this old, the first thing I check are the capacitors. They were mostly paper capacitors which I just replace outright since they usually fail.

For this restoration project, I want to keep the vintage look as best as possible. One way is to dress up the new capacitors in the clothes of the old capacitors.

In this picture you can see the metal cans containing the old capacitors and the new ones soldered on top for testing purposes.

Here I have used pliers to bend the flange back and remove the “lid.” The stuff inside is a wax that insulates and holds the actual capacitor roll in place.

The easiest way to remove it was to put a big wood screw right in and pull it out with pliers.

Now you can see what the roll itself looks like. It’s actually Kraft paper (like a very thin version of grocery bag paper) that has been vacuum deposited with an aluminum film. Two sheets are rolled up together producing the capacitor. The Kraft paper is impregnated with oil to increase the dielectric strength.

Here’s a larger one that I unrolled all across my workbench.

Notice how much smaller the new capacitor is. This fits easily in the metal can that once contained the old capacitor.

It was difficult to close the rolled metal lip without denting it, so it doesn’t quite look like the original, but it still beats ripping out the old capacitor or having the new capacitor squat on top like some sort of parasitic insect.

After recapping everything, it was time to strip down the chassis and get rid of the rust. I got rid of most of it, although there was a lot of pitting and such left over. I used Naval Jelly which does a good job of converting the original iron oxide (ugly red rust that spreads like gangrene) to iron phosphate (which pretty much just sits there). The grommets had all hardened and were crumbling off, so I replaced those as well.

Here’s a closeup of the back. You can see a few cardboard-roll style capacitors which have actually been gutted and fitted with shiny new capacitors on the inside. I sealed the ends using the old wax. Speaking of capacitors, I also had to replace two big electrolytic filter capacitors. The insides were filled with hardened pitch which I had to drill out to make room for the new capacitors, which were about 1/10th the size. Don’t you like the label?

This thing runs great now. I even dragged it out to the Maker Faire, but I didn’t plug it in for fear of wandering fingers (I left the cover off to expose the excellence inside).

June 18, 2008

Projects

1 Comment

Recently I obtained a vintage Clough-Brengle oscillograph. Yes, you read that correctly–the oscillograph is the predecessor of the oscilloscope. Oscillographs lack the trigger function and the calibrated vertical and horizontal scales, along with many other features now ubiquitous on the modern instrument.

First thing I did was pull the cover off to get a look at the innards.

Click the image to jump to the Flickr page which includes some notes describing the various parts of the oscillograph. There’s a lot of rust and grime from years of neglect.

There is more circuitry underneath the instrument, as shown in this photo:

A cluster of components forms the sweep oscillator of the Clough-Brengle oscillograph. The radial-leaded resistors are essentially carbon rods attached to wires and painted with colors indicating their resistance.

Color code for these resistors works as follows: The body color is the most significant digit, the end cap color is the second digit, and the dot on the body is the multiplier. The colors themselves have the same meaning as today.

These resistors are probably of the +/-20% tolerance variety. They are actually trimmed; a single gash in the side indicates where resistive material was removed during production to dial in the value.

For some reason this picture reminds me of a Frank Lloyd Wright building…

I’ll post some more pictures showing the restoration in progress. If you really must look ahead and see them, take a look at my Flickr photostream.

June 18, 2008

Projects

3 Comments

Here’s a genuine antique carbon filament light bulb. It’s 375 watts and was originally meant for 110 volts (currently in the USA we use 120 volts AC). In the photo, the bulb is running from 50 volts.

Perhaps someone out there has more information on the age of this bulb. I think it’s around 60-70 years old. It’s not older since it doesn’t have the glass seal on the top of the bulb.

This graph shows the resistance of the filament in two types of light bulbs. The blue curve shows that a carbon filament decreases in resistance as the bulb heats up, and the pink curve shows that a tungsten filament bulb increases in resistance as it heats up.

Thus, carbon filament bulbs have a negative temperature coefficient and tungsten filament light bulbs have a positive temperature coefficient.

Tungsten is the filament material most commonly used in household light bulbs.

Incidentally the curve for the carbon filament bulb stops short at 90V because I don’t want to damage it. It runs very, very hot!

June 18, 2008

Clocks

No Comments

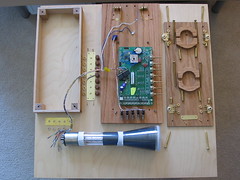

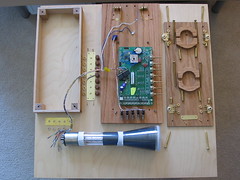

Here is my first scope clock ready for assembly. The CRT is a 3GP1.

After assembly.

June 18, 2008

Clocks

No Comments

This is my first Nixie clock. It uses four multiplexed tubes and includes an alarm feature which wakes me up every morning.

There is no snooze function, and the alarm will continue to beep until I shut it off.

The microcontroller is a PIC, coded in assembly. It uses the PIC’s 32KHz oscillator to keep the time.